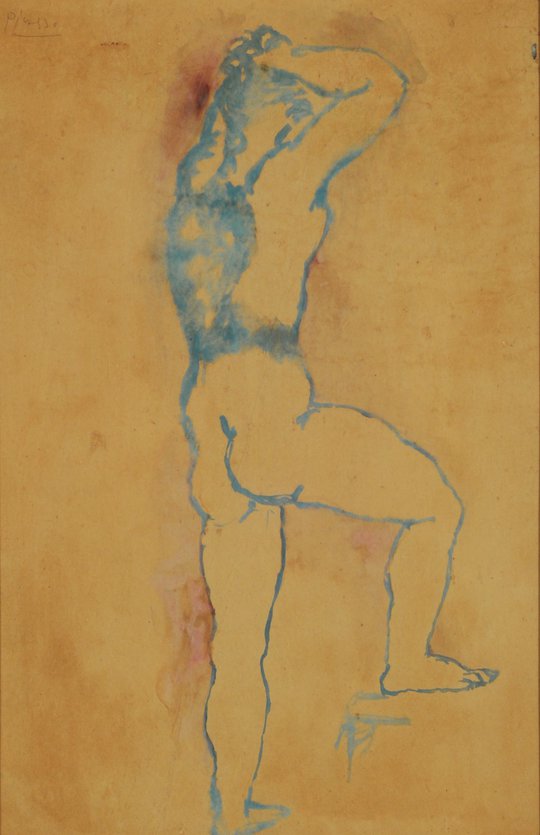

Femme nue de dos

Picasso, Pablo. 1905

More informationabout the work

Masterpiece

Accession Number 7967

Exhibited work

28

The theme of the nude permeates Picasso’s work and is as closely linked to his formal investigations as it is to his life’s most personal moments. His searches in the terrain of art and in the realm of passion intertwine and mutually foment one another, inaugurating several different periods in his work. The nudes in the MNBA’s collection point to two particular moments in his career. The small drawing from 1905 titled Femme nue de dos (Back of a Nude Woman, inv. 7968), which pertained to the collection of Paul Guillaume (1891-1934), a collector and promoter of French cultural life (1), corresponds to what art history has classified as his pink period, from 1904 to 1906. During these years he turns less to the humble and desperate as protagonists for his work, as he had during his blue period, and themes associated with harlequins and the circus appear. The harlequin is a typically modern theme, not a character left to his fate but in possession of his art’s power to transform. Picasso found that the circus and its characters were a theme that embodied the idea of the avant-garde artist perfectly. In this sketch, he portrays a standing young woman seen from behind, gathering her hair together with arms raised while resting one leg on what might be a cloth-covered stool. It is typical of a study made in the studio. It corresponds to a time when the artist’s finances and emotional life were both changing direction; when he moves to Bateau-Lavoir, exhibits the acrobat paintings, siblings Leo and Gertrude Stein begin to buy his work and his relationship with Fernande Olivier, who would be his companion and model during the next seven years, begins. The girl’s figure covers the paper’s limited space in a single, powerful plane without accessories of any kind, the body’s volume highlighted by way of red crayon accents. The figure exudes a certain classicism, a trait that appears in many of the drawings that he made in 1905 during his visit to Holland.This nude was done just two years before he would create his monumental cubist brothel, Les demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon) in 1907 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York), in which the female figure is one of the battlegrounds for the transformation in modern art language that we know as cubism today.Femme allongée (Reclining Woman, 1931) pertains to a different period. This is the beginning of an extensive series in which Picasso portrays Marie-Thérèse Walter, the young woman he met in 1927 in the Lafayette galleries when she was seventeen years old (2). This painting represents a moment of fusion of traits from previous nudes and those that dominate his 1932 series. Compared to the latter, Femme allongée presents a synthesis that recalls ideograms and distortions he introduced in works like Les Trois Danseuses (Three Dancers) from 1925, today in the Tate Modern collection in London. Distortions like these, which were esteemed by the surrealists—who reproduced the series titled Une Anatomie (An Anatomy) in Minotaure magazine’s first issue in 1933—took on a violent character with teeth, tongues and deformities that he used to represent his wife Olga Koklova’s face since 1908. His portraits of her had initially been marked by an influence from Ingres, but went on to representations where lovers threaten each another with ferocious tongues and teeth. These differ greatly from the Titian-like nudes in which he portrays Marié-Thérèse sleeping. John Berger points out: “what makes these paintings different is their degree of direct sexuality. They refer without ambiguity to the experience of making love to that woman. They describe sensations, especially the sensation of sexual pleasure… she is seen in the same way whether clothed or nude: as soft as a cloud, simple, full of precise, unending pleasure for his life and feelings, […] A visual image can reveal the sweet mechanism of sex more naturally […] At its most fundamental, there are no words for sex—only noises; but there are forms” (3). Femme allongée can be associated with the portraits of Marie-Thérèse in that it brings together the characteristic purplish and green hues from the paintings he made of his young lover. As opposed to the works from 1932, where line details the face and genitals, moving along the entire body, describing it through torsions that represent a range from rest to the sensual tumult of the body once exhausted, in this case line and patches of color are what demarcate fundamental features—the face, raised arms and breasts—that extend above what could be a couch or a blanket on a bed. Femme allongée is one of the first pieces in an extensive series that includes works like Femme nue couchée (Reclining Nude, 1932, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) or Jeune fille devant un miroir (Girl Before a Mirror, 1932, The Museum of Modern Art, New York). In the MNBA’s work, line and planes of color represent the young woman as if she were a landscape. In a later text, Picasso described his desire to express himself in concise ideograms: “I want to say a nude. I don’t want to make a nude like a nude. I just want to say breast, to say foot, to say hand or stomach. If I can find a way of saying that, it’s enough. I don’t want to paint a nude from head to foot, but just to be capable of saying that. That’s what I want. When we talk about this, a single word is sufficient. Here, the nude says what it is with simply a gaze, without a word” (4). This quote is an eloquent way of describing this work. It is a concise, schematic nude, defined only by the route of a line and areas of color that intersect and overlap in order to define the body’s form. The rectangular shape that dominates part of the composition recalls the form of a window whose light defines areas of the young woman’s skin that are almost white.This painting is a key piece in the series of metamorphoses that the body undergoes in Picasso’s hands, which served him in order to transform the language of art time and time again. It is far from the angular forms he used to define bodies during his cubist period, from the detailed classicism of the first portraits of his wife Olga, or the exasperation that characterized the portraits of Dora Maar in tears. This work exemplifies a model of facial representation that critics cite as that which Picasso would typically employ in his profiles of Marie-Thérèse (a fusion of forehead and nose into a single passage, a single volume) and also develop in his extensive series of sculptures in plaster, cement and bronze produced in his studio in Boisgeloup, Normandy. This hidden lover—because the artist was married to Olga and also because she was a minor—is associated with a moment of fulfillment and pleasure that lasted until 1935, when the instability of his marriage and the beginning of the war in Spain mark the beginning of a profound crisis. Femme allongée is the condensation of a moment of joyful plenitude and intense experimentation with form.

1— The work probably enters the Di Tella collection at the moment in which Guillaume’s widow was negotiating the collection’s transfer to the French State, between 1959 and 1963. Today, the collection is found at the Musée de l’Orangerie en París.

2— Guido Di Tella acquires the work from Kahnweiler. In a letter dated March 22, 1960, he writes: “In accordance with our conversation, I am pleased to confirm that we are sending the 1931 painting ‘Femme couchée’ by Pablo Picasso in consignment. We also hereby grant you with the exclusive option to buy it within the coming year at the firm price of US$ 80,000. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler”. Letter from Kanhweiler to Di Tella, March 22, 1960, ITDT Archive, CAV, Box 22. 1960- 1970 Collection. Di Tella probably saw the work and committed to acquiring it during the trip he made with Lionello Venturi to visit galleries in Paris, London and New York in March of 1960 in order to acquire 20th Century works to be included in the first public presentation of the collection his father had developed at the MNBA.

3— John Berger, The Success and Failure of Picasso. New York, Pantheon Books, 1965, p. 156-157.

4— Pablo Picasso in: Hélène Parmelin, Picasso says. South Brunswick/New York, A.S. Barnes and Co., 1966, p. 91. Author’s translation.

1962. Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1960-1962, dos anos y medio de actividad. Buenos Aires, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, [s.p.].

1985. KING, John, El Di Tella. Buenos Aires, Gaglianone, reprod. byn p. 68.

2006. ARTUNDO, Patricia M. (org.), El arte espanol en la Argentina 1890-1960. Buenos Aires, Fundación Espigas, reprod. color p. 452.

2008 [2001]. GIUNTA, Andrea, Vanguardia, internacionalismo y politica. Arte argentino en los anos sesenta. Buenos Aires, Siglo XXI, p. 107, 329.

Related works

A vast panorama of Argentinean art, including works by its greatest representatives

Browse collection ›Get to know the great works on exhibit, and more

Browse collection ›